9 Ways to Design Inclusive Content

Ready to see AudioEye in action?

Watch Demo

Learn what inclusive content means and how to put inclusivity into practice with your content efforts. This article was originally published by AudioEye’s Alisa Smith, CPACC on the Moz blog.

Inclusivity is an important consideration for every business owner and content creator, and should be at the heart of your ongoing design efforts — not something you look at after a website or piece of content goes live.

Before we get to specific tips on creating this inclusive content, let’s go over key definitions and concepts.

What is Inclusivity?

Inclusivity is about recognizing diversity. It ensures everyone can participate to the greatest possible extent. Other names for inclusivity include universal design and design for all.

Inclusivity addresses a wide range of issues, including:

- Accessibility for people with disabilities

- Access to and quality of internet connectivity, computer hardware, and computer software

- Computer literacy and skills

- Economic circumstances

- Education

- Geographic location

- Culture

- Age (older and younger people)

- Language

Understanding Usability, Accessibility, and Inclusivity

Usability

According to the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), an international standards organization that publishes guidelines and recommendations for web technologies, “Usability is about designing products to be effective, efficient, and satisfying.”

Usability factors measure the functionality of a product or design and the design interface’s ease of use. They assess how easy it is for users to learn the basic tasks of the interface, how quickly users can perform tasks on the interface, and whether users can remember how to perform those tasks after time away from the interface. Usability factors also consider whether the design satisfies users, and if there are errors in the interface, how severe those errors are, and the ease of recovering from those errors.

Think about Google’s search page design. When it first launched, it received considerable backlash. This was an era when internet users wanted their own “home pages” or “web portals,” each presenting their favorite news and links when the browser launched. But what did these portals all have in common? A search box. The fact that this simple (some still say ugly) design eventually became the homepage for billions of internet users speaks to the value of simplicity and how it enables inclusivity.

Accessibility

Designing with accessibility in mind means more people will be able to use a product, regardless of their abilities.

According to W3C, “Accessibility addresses discriminatory aspects related to equivalent user experience for people with disabilities. Web accessibility means that people with disabilities can equally perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with websites and tools.”

In other words, all users, regardless of ability or circumstance, should be able to:

- Perceive all interface or document elements.

- Operate the controls easily and intuitively.

- Understand the content.

- Use different assistive technologies, devices, browsers, and operating systems to interact with the content.

For example, using high-contrast colors in an app doesn’t just help people who have low vision or color blindness, it also helps people who use their devices in bright sunlight. Similarly, while improvements to usability, like using simple language and intuitive design, may allow people with cognitive disabilities to use a product or service more productively, they are also beneficial for people who may be busy or distracted, who are learning the language, or even people with slower internet access, because simple and intuitive sites may be faster to load.

Additional resource: Accessibility Principles, W3C

Inclusivity

Inclusivity means representing people who have, until now, been underrepresented. Inclusivity issues affect people from specific populations within a community, as well as communities that have been denied the opportunity to participate fully in economic, social, or civic life.

Inclusive content should always recognize diversity in the functional needs and abilities of individuals. To make your content inclusive, think of peoples’ diverse abilities, ensuring your content can be accessed in a variety of ways.

Inclusive content should also encompass diversity in personal needs and experiences. We should all challenge ourselves to do better at including different communities, identities, races, ethnicities, backgrounds, abilities, cultures, and beliefs. We must take steps to avoid “othering” people. By ensuring that everyone feels welcome in our digital spaces, we can more accurately represent the world we live in.

Additional resource: What is Inclusivity?, Diversity for Social Impact

Why Inclusivity is Important

History has taught us about the struggles for equity and inclusion globally. Wars have been fought over human rights and the rights of enslaved peoples. Women have protested for suffrage. People of color have long fought for civil rights, and in recent years the Black Lives Matter movement has highlighted systemic inequalities and the need for social justice. The Gay Revolution has sought to achieve equal rights for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. Indigenous people have struggled to gain equality and receive meaningful reconciliation for the abuse and mistreatment suffered at the hands of governments. And the Disability Rights Movement has worked to change attitudes, promote integration, and ensure that all people, regardless of ability, have equal access to transportation, housing, education, and employment opportunities.

While educational systems do teach us about these issues, they often present them as discrete events that have little real connection to the “dominant” society. As a result, most people are not comfortable speaking or writing about them. We simply do not have the vocabulary.

By making empathy an essential part of inclusion, business owners and content creators can improve their audience communications, build trust, and grow networks. Meeting the functional needs of all users creates a better reputation and improved word-of-mouth in more communities.

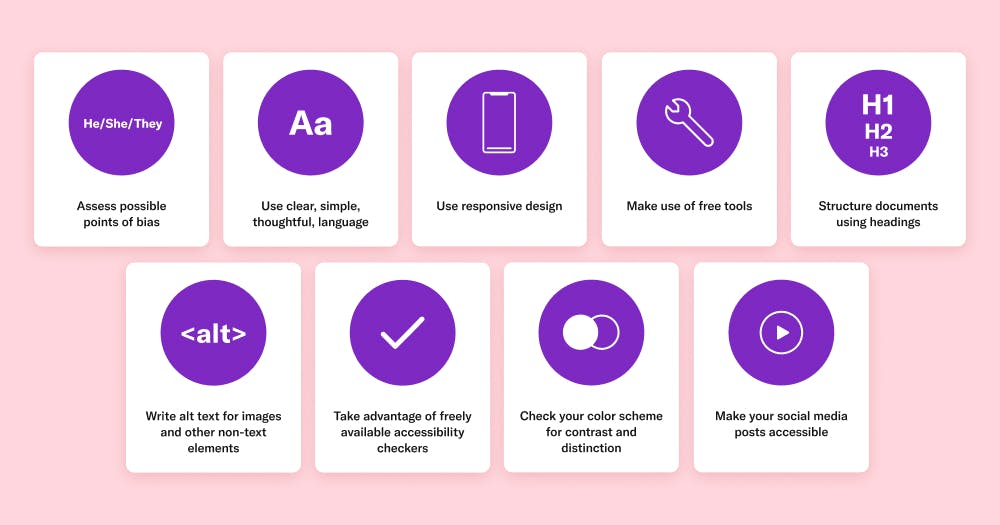

Nine Ways to Design Inclusive Content

Inclusive design should always meet the needs of as many users as possible. Use the following inclusive digital content tips when creating websites, mobile apps, e-mail, and documents.

1. Assess points of bias in your content and design practices.

Does your content default to the pronoun “he,” or does it make equal use of “she” and “they”? Review your text content, stock photography, and illustrations. Look at both digital and printed materials aimed at internal and external audiences. Do they feature mostly white, male, straight, non-disabled people? If so, it’s time to switch up the terminology and create a new aesthetic – one with more diversity.

Additional resources:

Resources for Eliminating Bias in Design, UX Booth

The Bias Blind Spot and Unconscious Bias in Design, Interaction Design Foundation

2. Use clear, simple, and thoughtful language.

Review words through the lens of inclusivity. Identify and remove all instances of othering and ableism. This boils down to respect. Avoid collective terms and labels, such as “females” or “the blind,” that group individuals into a category that promotes objectification. Always remember an individual’s disability, gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, or heritage is just a single facet of their unique and complex identity.

Disability

A disability is something that a person has. It is not who they are. Use “person with [a disability]” or “person who has [a disability].” Put the person at the forefront. For example, say “a person who is blind,” not “a blind person.”

Many people with disabilities prefer people-first language. However, there are also people with disabilities who prefer identity-first language, and it is important to respect this preference and give every person the self-determination to choose. Never correct someone who refers to themselves using identity-first language. For example, don’t correct or change the reference when someone calls themselves a “blind person” as opposed to “a person who is blind.��”

Avoid any language that suggests pity or hopelessness, or that disempowers people with disabilities, such as “suffers” or “victim.” Avoid words like “brave” or “courageous,” as these words can belittle or trivialize people with disabilities.

Gender

The male-dominated cultures of North America and Europe have created a biased vocabulary that should be adjusted for inclusion. It is common, for example, to refer to groups of people as “guys,” even when the group includes both men and women. Adult women are often “girls,” but adult men are rarely “boys.” Then there are the outdated words and phrases that have become problematic, such as “manpower,” “man-hours,” “man the controls,” or “man up.” Substitute these terms with “workforce,” “hours,” “take the controls,” or “step up.”

What should you do if you’re not sure how to address someone? Use the gender-neutral pronouns they/them/their when meeting someone for the first time. Here’s an inclusive way to introduce yourself, “I refer to myself as (she/her), what pronouns do you prefer?” or “My pronouns are (they/them), what pronouns do you use?”

Race and ethnicity

Just like the vocabulary of gender, words associated with race, ethnicity, nationality, and heritage have been debated over vigorously in recent years. A central part of inclusion is adopting terms that are honest and respectful and being intolerant of terms that are disrespectful. Historic bias has permeated our culture, and as a result, problematic terminology once used to describe people who are not white has been applied to many different areas of life, including technology (whitelist/blacklist, master/slave devices). Always address people’s ethnicity, nationality, or heritage respectfully and without irony, racism, or satire.

Additional resources:

Diverse Abilities and Barriers, W3C

3. Use responsive design that allows zoom and orientation changes.

Responsive design allows web content layouts to display well on many form factors, using “breakpoints” to define different widths. Sometimes app makers lock orientation or turn off the zoom ability. These are basic tools that we all need from time to time. Instead of disabling them, design apps to accommodate them.

Here are a few responsive design and accessibility guidelines:

- Use link text that describes the link destination.

- Write meaningful and descriptive alt text.

- Use semantic HTML – tags that clearly describe the purpose of page elements, such as <header>, <article>, <aside>, or <footer>.

- Instead of fixed or absolute font sizes, use relative units for font sizes, such as percentage units, viewport width, or viewport height.

- Label all buttons and fields.

Using responsive design and accessibility guidelines makes it easier for search engines to crawl and interpret websites. For example, sites with clear, descriptive headings – the same kinds of headings that also make navigation and comprehension easier for people for disabilities – are better optimized for search engines to do their work.

Because of this, Google rewards accessibility when ranking websites. In fact, their Webmaster Guidelines – which lay out the best practices that help Google to find, index, and rank your site – read very much like accessibility guidelines, and often correlate directly with the W3C’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

By using accessible design, you are simultaneously improving the on-page experience, making your content more accessible to users with disabilities, and facilitating the work of search engine bots who are busy crawling, indexing your site, and assessing link equity between pages – all of which help boost your SEO ranking.

Additional resources:

Responsive Design, Mozilla

4. Take advantage of free resources.

Testing is an integral part of developing accessible and inclusive digital content. Fortunately, tech companies have created a range of tools and resources to help ensure your documents, websites, and apps can be accessed easily by all users. For example, Microsoft Office applications – Word, PowerPoint, or Excel – have the Check Accessibility feature, which resides in the Review menu. From there, you can choose the ‘Check Accessibility’ button and follow the instructions to remove accessibility problems, rechecking as you go until all issues have been addressed.

Additional resources:

Design for Inclusivity, Microsoft Design

Accessibility for Developers, Apple

Developing for Accessibility, Google

5. Structure documents using headings.

Use simple, hierarchical headings to organize documents, web pages, or emails. This allows all users and their technology to interpret the main ideas of the content and find the information they’re looking for. Graphics should be secondary and should never contain critical information. Provide equivalent alternatives for any image that contains text.

Also be sure to include a link to the web version of any HTML message right on top, in case of e-mail client issues with layout or graphics. If you’re using HTML messages, then follow basic, semantic HTML best practices. E-mail is the only technology where tables for layout is still acceptable, but even there, CSS is now preferred.

Evaluate your content without graphics or with the graphics turned off. This will ensure your content can be accessed on low-fi devices, over bad connections, or through a screen reader.

Additional resources:

Web Accessibility – Headings, Yale University

6. Provide text alternatives for non-text elements, such as images and forms.

Use simple, descriptive language as alt text for images. If the image serves a specific function, the alt text should explain what that function is and describe the contents of the image. The goal is to ensure that everyone has access to the same information about the image.

If the image contains a chart or graph, the alt text should include the data. If you’re using a creative photo or a photo as an illustration, the alt text should describe the elements of the image in detail.

If the document or content includes images that are not important, are used for layout, or do not serve a specific function, use null alt text (alt=“”). This will keep them hidden from assistive technologies.

Labels for form fields and options are also areas where inclusion and accessibility should be addressed. Every field and button should have a label, written in plain language. If button labels have icons or images, the alt text should describe the function of the button, rather than its appearance.

When creating contact forms, label all fields visibly. Include formatting hints to reduce errors. If you use a placeholder, ensure that it stays visible.

Additional resource:

7. Take advantage of freely available accessibility checkers.

Check your content regularly to keep it inclusive and accessible. Every time you make changes to your website, you run a risk of making content inaccessible to people with disabilities. This is why ongoing monitoring is important. AudioEye, a digital accessibility platform, offers Active Monitoring to help site owners keep their content accessible and inclusive. AudioEye checks for accessibility issues every time a site visitor loads a new page. It also tests for new accessibility issues, gathering information across all users and pages, and then automatically fixes the majority of common errors. AudioEye’s technology can find about 70% of common accessibility issues, using 400+ testing outcomes, and resolve about two-thirds of them with a suite of more than 70 automated remediations. The platform displays all accessibility issues found and fixed in an Issue Reporting dashboard, along with details on how these issues affect users with disabilities and how to fix unresolved issues that require human intervention. You can start by trying AudioEye’s Accessibility Checker.

Additional resources:

Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools List, W3C

Testing and Checking Content, Accessible Social

8. Check your color scheme.

Assess the color scheme for contrast and distinction. White text on a black background is high contrast, while white text on a pale blue background is low contrast. Many people with visual disabilities rely on high color contrast to view digital content. And because visual acuity and the ability to distinguish colors also fade with age, high color contrast ensures older users can access your content.

Common color choices, such as buttons colored red and green, can make content inaccessible to people with color blindness, which affects 13 million Americans and 350 million people worldwide.

Additional resources:

What is Color Contrast and Why Does it Matter For Website Accessibility?, AudioEye

Deuteranopia – Red-Green Color Blindness, Colblindor

Color Contrast Checker, AudioEye

9. Make social media posts accessible.

Social media is used to convey messages or ideas quickly, usually in just a line or two of text, using a single image or a short video. To meet accessibility requirements for social media, ensure that all images and video clips are described in detail. Include voiceovers, narration, and song lyrics in the description. Don’t forget to include the emotion the subject may be trying to evoke. This also helps low-bandwidth users participate in social media.

Assess the cast of your videos. Do they feature mostly white men? Look for ways to feature a broad cross-section of society, including different genders, people of different ethnicities, and people with disabilities.

Emojis make social media posts fun, but they can also pose problems for people who can’t see them. Because screen readers use words to describe the emoji, a series of smiley faces and hearts added in the middle of an Instagram caption becomes “grinning face, smiling face with smiling eyes, smiling face with heart-eyes, red heart, red heart, red heart.” Limit your emojis to two or three, and put them at the end of your text, so they don’t get in the way of the information in the post.

Hashtags are an essential part of social media posts: highlighting key words and phrases with # makes it easy for users to find posts. Making hashtags accessible is simple: capitalize the first letter of each word in the hashtag (also known as CamelCase). That helps screen readers separate the words correctly (#SuperBowl, not #SuperbOwl) and to say them as words, rather than as separate letters.

Additional resources:

How to Make Your Social Media Content More Accessible, Western Oregon University

Hashtags, Accessible Social

List of Emojis, Emojipedia

Designing Inclusive Content is an Ongoing Effort

As you start applying these best practices, remember that building accessible, inclusive, and usable content takes dedication and continuous improvement. Ask your site visitors and customers for feedback on a regular basis. Pick the right tools to make your efforts more sustainable and effective.

Ready to see AudioEye in action?

Watch Demo

Ready to test your website for accessibility?

Share post

Topics:

Keep Reading

7 Websites That Got Accessibility Right (and What You Can Learn)

Looking to create an accessible website? See how seven companies utilized accessibility best practices to create a seamless user experience that works for all.

accessibility

April 11, 2025

Why People + Automation Is the Right Approach to Accessibility Testing

Discover how using both automated and manual accessibility testing is the perfect approach to creating accessible, compliant digital content.

accessibility

April 08, 2025

Is WCAG Certification Possible? 6 Things You Need to Know

While WCAG standards don’t offer official certification, there are training programs and professional credentials that can boost your accessibility expertise. Learn more.

accessibility

April 03, 2025