How Screen Readers Make Digital Content Accessible

- How Do Screen Readers Work?

- Screen Reader Customization

- Language and Accent Modification

- Scripting Functions

- How Do People Use Screen Readers?

- What Kinds of Screen Readers Are There?

- Built-in and Online Screen Readers

- Online Screen Readers

- JAWS (Job Access with Speech)

- NVDA (NonVisual Desktop Access)

- ZoomText for Windows

- Should My Employees Learn to Use a Screen Reader?

- Designing a Website for Screen Reader Accessibility

- Moving Toward Comprehensive Digital Accessibility

- Screen Reader Demos

- W3C/WebAIM Resources

What Is a Screen Reader: A Guide to Making Digital Content Accessible

Ready to see AudioEye in action?

Watch Demo

Screen readers are software that enables those who cannot see the screen to access information on computers and smartphones. The technology reads the screen aloud or converts it to Braille.

Originally Posted: 04/05/19

Almost 20 million Americans (8 percent of the U.S. population) have some type of visual impairment. Visual impairment, including blindness, low vision, and color blindness, make using the internet incredibly difficult. This is why many of these individuals rely on screen readers to navigate the web.

While most screen readers are used by people who are blind or have low vision, they’re also used by people with learning disabilities or those who prefer not to view visual content for various reasons.

With a huge number of people relying on screen readers to use the web, it’s important to keep screen reader users in mind when creating a website or other digital content. Below, we’ll delve into everything you need to know about screen readers and how to design content that works well with assistive technologies.

How Do Screen Readers Work?

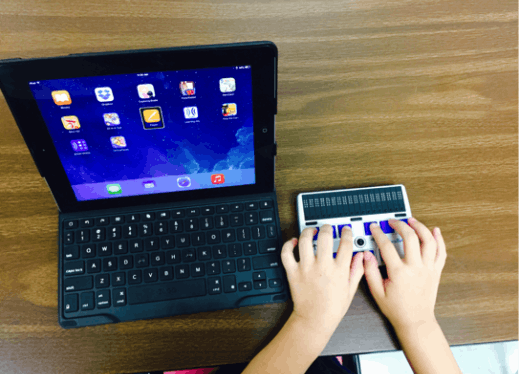

Screen readers convert text displayed on a computer into a usable format for those who cannot read it. Users navigate their devices through a variety of keyboard commands and unique shortcuts.

Typically, screen readers work in one of two separate forms:

- Text-to-Speech Output: This is where words are read directly to the user

- Braille Display: Users read the output through a tactile pad that translates the words into Braille

In addition to reading text from the computer screen, screen readers can translate pictures and tables to help the user make sense of every element on the page.

Screen Reader Customization

Screen readers can be customized based on the user’s needs.

For example, users may choose the verbosity (wordiness) setting on their device that directs how much detail they want to receive. A lower verbosity level may omit some punctuation and detailed information about the page’s structure, providing a more natural user experience.

Since screen reader output can change depending on the user’s settings, it’s extremely important to build content that works for every type of user. That means following the principles of semantic web design (in this context, ‘semantics’ means defining each element so that different types of technologies can identify it).

Language and Accent Modification

Screen readers typically support more than one language, so the technology can switch to a different language as long as that language is encoded in the site’s metadata.

This also means that screen readers can read content in an appropriate accent. For example, if a website is from the United Kingdom, the screen reader can use U.K. pronunciation rules to output the content accurately.

Scripting Functions

Screen readers can be tailored to the user’s unique needs through scripting. Scripting is the ability to write programs that automate tasks in certain environments.

Users can use scripts for a more natural browsing experience and share these customizations with other users. Many screen readers have an active script-sharing community to help all users get the most from their software.

How Do People Use Screen Readers?

Contrary to a popular misconception, screen readers are not web browsers. Screen-reading software works “on top” of web browsers (such as Mozilla, Firefox, Apple, Safari, and Google Chrome) and other applications.

The most popular screen readers support braille output, but not all people with vision disabilities can read braille. According to a 2019 WebAIM (Web Accessibility in Mind) survey, only 3.9% of users said they “primarily rely on braille output”, while 71.3% said they “exclusively rely on screen reader audio.”

Screen readers rely on various keyboard commands to navigate the page based on heading structure and link text. Typically, screen readers will start reading text at the top of the screen, but users can skip to the content they’re looking for via keyboard shortcuts and commands.

However, if a website isn’t designed for accessibility, using a screen reader can be frustrating. The software might read text out of order, or the user may be unable to fill out forms or easily navigate content.

For an example of how screen readers output content, read ‘A Screen Reader User’s Take on Google’s Homepage’.

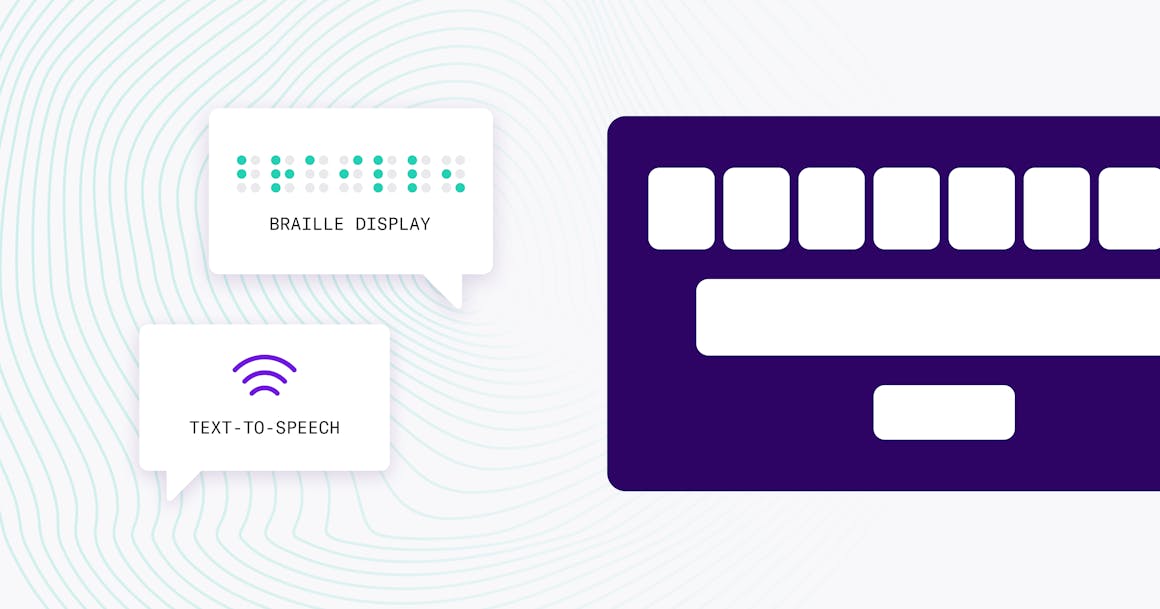

What Kinds of Screen Readers Are There?

Screen readers are available on both desktop and mobile devices:

- Desktop: Most desktop operating systems have built-in options; however, most screen reader users prefer dedicated software such as NVDA (NonVisual Desktop Access) and JAWS (Jobs Access With Speech).

- Mobile: Both Android and Apple iOS feature built-in screen readers (TalkBack and VoiceOver) to help visually impaired users navigate the web on their mobile device.

Typically, most users decide on one type of screen reader and stick with it. This is primarily because each application has distinct features and learning the software takes time.

Mobile and desktop devices are just some assistive technologies that help visually impaired users navigate the web. We’ll discuss additional types of screen readers below.

Built-in Screen Readers

Most operating systems have built-in (or native) screen readers. For example, all Microsoft Windows operating systems after 2000 include Microsoft Narrator. While Narrator has come a long way, it has limited functionality, and most users prefer third-party software.

Apple products (macOS, iOS, and tvOS) include a feature-rich screen reader called VoiceOver. VoiceOver (Zoom) can also magnify the screen for users with low vision. Google Chrome OS features a native screen reader, ChromeVox, which can be added to the Google Chrome web browser via a free extension.

Artificial intelligence (A.I.) voice assistants (such as Apple’s Siri, Google Assistant, and Amazon Alexa) also have certain screen reading capabilities, which can improve experiences on mobile operating systems. However, dedicated mobile screen readers like Android TalkBack and VoiceOver (for iPhones and iPads) provide improved usability and more options than standard voice assistants.

Online Screen Readers

Some screen readers can be accessed online; for example, web pages such as WebAnywhere and Spoken Web allow users to access screen reading capabilities through an online portal.

These tools feature a simple interface, which allows users to navigate easily between elements and hear article content in a clear manner. Although their capabilities are somewhat limited, these portals are especially useful for individuals who do not have the capability to download software onto a computer.

JAWS (Job Access with Speech)

Developed by Freedom Scientific, JAWS is the world's most widely used screen reader. The application supports Windows operating systems and features multi-screen support, integration with Microsoft applications (such as Microsoft Office), touch screen and gesture support, and compatibility with braille displays.

NVDA (NonVisual Desktop Access)

NVDA is a free, open-source screen reader for Windows operating systems. According to WebAIM’s screen reader user survey, NVDA is currently the second-most popular option.

Like JAWS, NVDA supports braille displays and is compatible with Microsoft applications. The software can output audio in 55 languages, and the NV Access website includes tutorials and other training resources to help users configure the software.

NVDA can also load from an external storage device (such as a USB drive), which makes it an excellent option for students and people who use public computers.

ZoomText for Windows

Designed for users with low vision, ZoomText is an integrated screen magnification and reading program. It is available in three versions: magnifier; magnifier plus reader; and magnifier with all the screen reading software.

In WebAim’s 2021 survey of screen reader users, 4.7% of respondents said they used ZoomText as their primary desktop/laptop screen reader.

Should My Employees Learn to Use a Screen Reader?

Organizations that are new to digital accessibility may want to make sure that their website is compatible by checking it on an actual screen reader.

However, developing skills with a screen reader takes time. If you don’t use screen-reading software regularly, testing your content with JAWS or NVDA may lead to false negatives (missing accessibility issues) and false positives (finding issues that aren’t problematic for regular users).

Additionally, screen reader output can vary depending on the user’s web browser, operating system, verbosity settings, and other factors. Screen reader tests should be performed by experienced accessibility experts — ideally, people who have spent years working with JAWS, NVDA, and other popular screen readers.

Designing a Website for Screen Reader Accessibility

Published by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 guidelines are the international standard for web accessibility It’s also an excellent primer on the essentials of web design.

WCAG addresses the most common issues that impact users with assistive technologies, including:

- Missing alternative text (alt text): Missing alt text prevents a screen reader user from understanding the purpose of images, graphs, and other non-text content.

- Poor keyboard accessibility: Without robust keyboard accessibility, users may be unable to navigate a web page.

- Redundant and “empty” hyperlinks: Missing hyperlinks can limit navigation and confuse assistive technology users.

- Missing captions and transcripts: Without captions and transcripts, screen reader users cannot consume multimedia content.

- Improper use of headings and subheadings: Headings with vague or improper HTML markup limit users’ ability to navigate a page.

It’s important to note that WCAG is written to improve experiences for all users with disabilities — not just blind people and individuals with low vision. Testing your content against the guidelines can improve compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and other non-discrimination laws.

And because WCAG supports the best web design practices, conformance has other benefits: Accessible websites tend to perform better in search engine rankings, attain higher conversion rates, and provide a better experience for all users.

Moving Toward Comprehensive Digital Accessibility

Organizations should keep screen reader users in mind when creating a website or other digital content. To help you do this, there’s AudioEye.

AudioEye’s digital accessibility platform is designed to help organizations of every size meet their digital compliance goals. Our technology scans content for common accessibility barriers, remediating many issues as the page loads.

We also provide options for expert testing, expert-led remediations, and a 24/7 help desk to help you find (and fix) the barriers that impact your users.

To learn more, book a free demo.

Screen Reader Demos

W3C/WebAIM Resources

Ready to see AudioEye in action?

Watch Demo

Ready to test your website for accessibility?

Share post

Topics:

Keep Reading

Improving Healthcare Delivery: How Quality Tech Products are Shaping the Future of Care

Discover how high-quality tech products are transforming healthcare delivery, improving patient outcomes, and future-proofing the industry. Learn key tech innovations and why accessible, inclusive design is critical.

accessibility

March 26, 2025

Why an Accessibility Widget for Your Website Isn’t Enough — and What to Do Instead

Widgets seem like an easy way to ensure compliance with accessibility regulations, but your site/app needs more than they offer. Here’s how to approach it.

accessibility

compliance

March 25, 2025

The Hidden Accessibility Violations in Online Documents

Hidden accessibility violations in PDFs can create major barriers for users with disabilities. Learn how to identify and fix common document accessibility issues to ensure compliance with accessibility laws.

accessibility

compliance

March 21, 2025